“We’re now seeing the transition we’ve been expecting. After five years, ebooks is a multi-billion dollar category for us and growing fast — up approximately 70 percent last year. In contrast, our physical book sales experienced the lowest December growth rate in our 17 years as a book seller, up just 5 percent.”

The book publishing conference season is in full swing and “discovery” is the buzzword du jour, driven by the curious notion that, with the decline of physical bookstores, readers supposedly can’t easily find books online. There’s even new research that claims “frequent book buyers visit sites like Pinterest and Goodreads regularly, but those visits fail to drive actual book purchases.”

Unfortunately, in the spirit of “lies, damned lies, and statistics,” that research is skewed partly by its authors’ underlying agenda (“Physical retail works if you protect it.”), but more importantly, by its flawed methodology, specifically its dependence on what’s known as last-click attribution, wherein the final interaction that led to a sale is given 100% credit for the conversion, ignoring the realities of multiple touchpoints and myriad potential influencers.

The problem is that this assumes that people are waaaay less complicated than they really are. Very few people buy anything after one brand interaction. We’re comparison shoppers. We want the best deals. I don’t buy anything until I’m sure I’ve found the best item at the best price.

–“The Death of Last Click Attribution,” Kimm Lincoln

Never mind the folly of dismissing Goodreads, a social network dedicated to books with 13m+ members and steadily growing, or even Pinterest, where Random House has inexplicably attracted 1.5m followers, but the very idea that “something is really, chronically missing in online retail discovery” is arguably contradicted by Amazon’s 2012 results, suggesting that “online retail discovery” isn’t really a problem for readers.

It’s a problem for publishers.

METADATA: NOT THE UNICORN YOU’RE LOOKING FOR

Metadata is important. Few would argue otherwise.

But it’s a foundational piece of the puzzle, like saying “publish good books.” If we can’t get these basic steps right, then game over, turn off the lights, go home, and let the algorithms have at it.

Publishers will never beat Amazon at SEO. Hell, B&N can barely keep up with them, though I’ve noticed Goodreads is often in the top 5 results in my own searches. Where publishers might have a shot is in narrow niches that are typically ignored because they don’t generate bestsellers, but they’re more likely to lose out to their own authors and organic interest communities anyway, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Meanwhile, every eager startup with some bootstrap funding and an angle on getting books indexed by Google that suggests otherwise are either lying to themselves, or are lying to the publishers they’re attempting to “partner” with as they position themselves for acquisition.

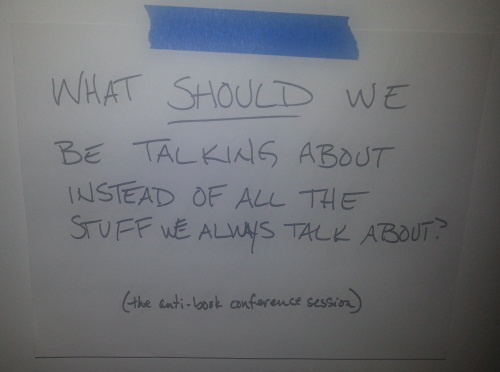

At Book^2 Camp yesterday, I asked point blank what happens when all publishers have the ideal metadata and all of their books are indexed by Google? The answer was, effectively, nothing. The playing field is once again leveled (though Amazon and Google will still live at the top of hill), and the underlying problem, an ever-increasing glut of content, will remain unaddressed.

THAT THING WE SHOULD STOP TALKING ABOUT, AND JUST DO IT

“Fewer, better books.”

At some point in every conference, often more than once, somebody says it, we all nod in agreement, and yet, the output from “traditional” publishers continues to grow, or at least remain steady, each year. In the final years of the “bigger is better” era, investors demand it, budgets quantify it, and the bad decisions continue to pile up.

One of the first articles I published back when I was running Digital Book World was written by F+W Media’s CEO, David Nussbaum, wherein he explicitly made the bold claim himself: “Produce fewer, but better books.”

Not surprisingly, he caught a lot of flak for that post because his proposed solution, “eliminate the mid-list,” seemed rather draconian, and while he clarified in the comments that what he meant was “middling product,” I think many would argue that publishers have mostly leaned in the direction of his original wording.

More Snooki, less mid-list, and the ice gets thinner and thinner.

KNOW THY READERS; SERVE THY READERS

One of my biggest frustrations with publishing conferences is the preference for harping on what publishers are supposedly not doing, instead of spotlighting those who are doing plenty, and doing it successfully.

Some forward thinking publishers (Osprey, Sourcebooks, Constable & Robinson, F+W Media and the like) have already begun to segment their lists into easily definable verticals. The next stage is to target the consumers who inhabit those verticals and to do that they will need to have strategies in place to leverage the market intelligence derived from ‘big data’ by using modern marketing techniques such as SEO and social media management.

–“Vertical Publishing. Take it to the people.” Chris McVeigh

Of course, “verticalization” gets thrown around like some kind of unicorn, too, and while I’ve noted in the past that there are plenty of pitfalls along that path, at least it’s a viable path, with plenty of success stories, and is far less reliant on the hit-or-miss, gamble-by-committee, no accountability approach that seemingly drives a lot of acquisition decisions these days. At least in the big houses.

The publishers who have a direct relationship with their readers — not necessarily via direct sales, but via direct engagement — are the ones who will not simply survive the “digital shift,” but will thrive, being less prone to the whims of Amazon, Apple, Google, or whomever the next big tech player might be. Readers won’t have any trouble discovering their books, old or new, nor will they have any obstacles to spreading the word to their friends about those books.

Publishers lacking that relationship are the ones with a discovery problem, and the clock is ticking…

Do you like email?

Sign up here to get my bi-weekly "newsletter" and/or receive every new blog post delivered right to your inbox. (Burner emails are fine. I get it!)

I always appreciate your posts and admire how you turn words, and there’s in this particular post I agree with. But a few assertions struck me as a reach or maybe even involving spurious reasoning.

The issue around discovery is not readers can’t find books online; of course they can. It’s never been easier to find a book you’re looking for. The question, at least in my mind, has more do with the quality of what you discover online. I also don’t think Amazon’s 2012 results count as evidence one way or another about this dimension of challenges that online discovery may create for readers. It just shows that Amazon doesn’t have a problem with discovery. Yes, publishers have a problem with discovery; I’d say authors do to. Whether readers have a problem with discovery is conjectural.

That said, I’d offer that the channels of discovery of quality books is and will be challenged due to the volume of books being “published” digitally and in print. The oft cited figure of an increase if ISBNs to 33M up from 2.5M just a few years ago doesn’t even take into account the number of self-published eBooks, which largely don’t include ISBNs. It is conjectural, I admit, but it seems pretty clear that the size of the haystack must have some effect on how easy it is to find the needle.

Later on in the post you suggest that publishers would be better off if they published “fewer, better books.” But I don’t think reducing the number of books will necessarily reduce the number of “bad decisions” that acquiring editors might make. Self-publishing is making traditionally published books a smaller portion of the market segment while number of book consumers is flat to down. Is fewer books really the way to go? Maybe, but I’m not sure it addresses any of the key problems facing publishers, unless cutting title counts allows them to dramatically reduce their overhead and invest that more fruitfully elsewhere.

You’re not really saying anything here that I haven’t addressed in this post (an admittedly hasty one that arguably tries to cover too much ground), or at various points in the past, and not really offering any clear points of disagreement for conversation or debate.

IMO, the implication of “fewer, better books” is very clear: focused lists and the ability to market them all effectively. If you know your readers and have a direct relationship with them, that’s a very viable model that plenty of publishers follow. It’s the opposite of the corporate spray-and-pray model that’s overly reliant on the homerun to offset many, many strikeouts.

Thanks for the reply. I guess I wasn’t all that clear. What I was trying to say about discovery is that there is no way to tell if readers are not having trouble with it. On “fewer books” I was trying to say that publishers who do this run the risk of not increasing sales of titles they do decided to publish and market and simply loose market share. I’m not advocating one way or another, just trying to highlight that it’s a strategy with risks.

Very good piece. I think publishers are still having difficulty understanding just how much the world they live in has changed. Discovery is the wrong word – what the real problem is is “audience”. I am not sure the quantity and quality of books would be a problem for publishers if they knew how to target and attract the right audience for those books. Publishers need to start thinking more like magazine publishers and begin developing and marketing their editorial voice. The Big 6 are so merged and diluted that any voice Knopf or Scribners had is indistinguishable from the dozen other imprints they share. Verticals like F+W mean targeting audience by topic, genre and interest thus consolidating potential purchases into an audience predisposed to buy similar books. Publishers need to start thinking like TV and radio building direct links to identifiable consumers and herding them into groups that can be marketed to.

Yes. The lack of distinctive editorial voices is definitely an obstacle, and as Bob Miller noted, it leads to a lack of accountability as acquisitions are made by-committee in service of a budget that’s not tied to reality.

It’s not surprising that companies like F+W and Rodale have solid magazine units, while on the fiction side, it’s the genre publishers who are having the most success with direct engagement.

100% correct: readers have no Discoverability problem.

Readers know how to find good reads at good prices and if they don’t they quickly develop a strategy that works for them.

There is no “discoverability problem”.

What publishing needs to face up to is that *writers* have a *visibility* problem.

That publishers have a *marketting* problem. (As in most of them don’t do it. And no, coop placement fees to bookstores is not marketting. It’s “pay to play”; payola to be brutally honest.)

All the talk in the industry about consumers is as if they were some alien form of life that is unpredictable and unapproachable. Which they might as well be for all the attention publishers paid consumers during the gatekeeping era. But now that era is over and the need to effectively engage the attention of readers is masked with hand-wringing over discoverability.

By focusing on the one thing they have no control over, consumer habits, the industry gets to talk endlessly without having to actually *change* anything in their time-honored practices.

And they get to blame it on the consumers.

Nice and comfy.

Specialty publishers such as those listed above have no discoverability problem because they have strong brands with high visibility in their chosen market. They have built their brands through quality targetted content to the extent the brand often overshaddows the author. And their brand has its “one thousand true fans” and more.

Not all publishers can do that but they really need to do more than just crank out “quality” books one after another and hope somebody notices it during the five minutes it is featured on this talk show or that.

Building an identity for the brand is a pretty basic exercise for most businesses but one that most of the bigger publishers have forgotten about as they merrily commingle celebrity exploitation with litfic with current affairs or even cookbooks without attention to who is buying or why. All they care about is whether a lot of somebodies want to buy it without regard to who those somebodies might be, why they bought, or how to bring them back for more.

Simply put, most publishers have neither the mindset nor the skillset to deal with the age of abundance we are now entering. They would be well advised to look into a mirror for solutions instead of trying to project their internal problems into a mythical externity.

Before a solution can be found, you need to identify and acknowledge the real problem.

Discoverability?

Try brand-building and marketting and see if visibility is still a problem.

Amen! Bravo! And thanks for the comment.

Guy, I’d be interested to hear what you think of the model Twelve has followed since 2005. When they launched, I applauded their vision because, during my years in publishing, the push was always to publish as many books as possible to occupy as much shelf real estate as possible. They did this without hiring more editors, artists, designers, etc. to compensate. As result, those publishers I worked for are now on the verge of collapse. (I own my own company now, thankfully.)

It’s simple. You’re only as good as the content you produce, and if you’re constantly pushing your staff to edit, design, market, and sell more books than they can handle, the quality of what you produce and you’re ability to market it (as you suggest above) will suffer. If you’re publishing subpar material, it might not be in your best interest to be discovered.

I’m familiar with Twelve’s model, which I like in theory, but I don’t really know any of their books off the top of my head. Poking around their site to refresh my memory, it appears that what defines them is their business model and not the actual books they publish nor any particular segment of readers they appeal to. It’s like an odd variation on “spray and pray,” where they’re taking one deliberate shot at a time, but not at any particular target.

“If you’re publishing subpar material, it might not be in your best interest to be discovered.”

I think that right there is the real crux of publishers’ discovery problem.