Here’s an example, just a little sample

How I could just kill a man!

One-time tried to come in my home

Take my chrome, I said “Yo, it’s on

Take cover son, or you’re ass-out

How you like my chrome?”, then I watched the rookie pass out

Didn’t have to blast out, but I did anyway…

Hahaha… that young punk had to pay

So I just killed a man!

I’ve never been a fan of military shooters, partly because I served in the Army with people who actually lived the real experience, and partly because I value a tight, engaging story far more than “realistic” gunplay.

I’ve written before about how much Call of Duty’s simple-minded, “There Is A Soldier In All Of Us” commercial pissed me off, so much so that it helped me find the right ending to a poem about my own experience in the Army, several years and revisions after I’d first written it. Colin Campbell’s intriguing peek behind the scenes at the cannon fodder in the latest iteration of the Battlefield franchise, Hardline, gets to the heart of another problem I have with them, if coming up just short of putting a stake in it.

“So you have an opportunity to hear more from them. In some cases we made them too charming and people felt bad about shooting them or wanted to hang out with them instead of fighting them and that is no good.”

God forbid a player’s immersive experience be “interrupted” by the possibility of feeling empathy for even one of the potentially hundreds, or thousands, of virtual humans they’re going to kill throughout the game’s storyline! Pandering to juvenile power fantasies with incredibly detailed virtual replicas of a variety of weapons of mass destruction and highly destructible environments leaves no room for three-dimensional characters or any moral grey areas.

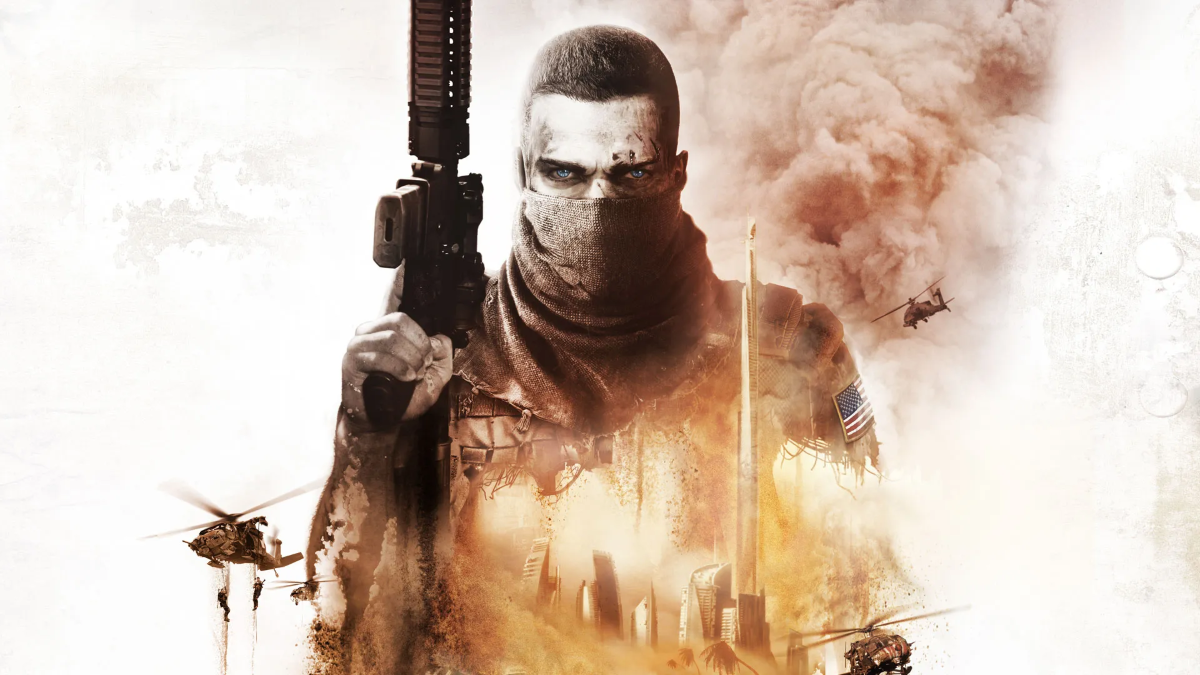

RPGs, simulations, and strategy games are my preferred genres, but I’ve played and enjoyed several shooters that prioritized story over gunplay (BioShock Infinite); explored the moral gray areas of violence as a solution (Spec-Ops: The Line),;or whose sci-fi settings simply put things in a less problematic context (Halo).

The timing of Hardline‘s switch from military fantasy to militarized police fantasy couldn’t possibly be worse, either, in light of the ongoing problems in Ferguson, MO, one of the more egregious examples of a systemic cultural problem in this country that most video games either completely ignore or cynically tap into.

*cough*GTA*cough*

Welcome to the Edge of Civilization

BUT… how then to explain Titanfall‘s appeal? I enjoyed the hell out of that game which made its own controversial decision to eschew story completely, making your avatar a hollow shell for a handful of statistical archetypes and putting the focus squarely on delivering engaging gun and gameplay. And did it ever!

It’s one the few video games I’ve ever put more than 100 hours into—hello, SimCity, Civilization, Madden, FIFA!—and it’s the only military-esque shooter that not only hooked me, but that I’ve been okay with my son playing. (I also purposefully had him play Spec Ops: The Line, and he found it as morally challenging as I’d hoped.) What really worked for me in Titanfall is your character isn’t some idealized superhero destined to save the day, but a nameless cog in the war machine who has to work with others and who is pretty much guaranteed to die, only to be replaced by another cog, like an endless stream of cloned Stormtroopers.

While there is an underlying story to Titanfall, there’s arguably no explicitly good or bad guys, and you could easily make a case for the Interstellar Manufacturing Corporation or the militia being the good, or bad, guys. By letting you play both sides in its slight “Campaign” mode, and randomly assigning those sides in co-op mode, the game pretty effectively eliminates context and puts the focus squarely on gameplay, while leaving enough room for players to imprint their own stories onto the action.

Personally, I preferred militia, and even bought a t-shirt to declare my side!

Sometimes a Fantasy. Is All You Need.

For a game to perfectly correlate gameplay to the narrative, the developer would need to surrender the power that they have over the story and put it in the players’ hands. This would require the creators to focus on molding a world where anything could happen. Essentially, it would ask that the developers not care so much about providing the experience that they visualized, but rather that they provide the means for an experience to occur. The rest is out of their hands.

Ludonarrative dissonance: The roadblock to realism, by Brett Makedonski

Ludonarrative dissonance might be the most fascinating concept video games ever introduced me to, but it’s not at the heart of my problems with military shooters. I used to complain about them the same way I did about people wearing camouflage attire: join the fucking Army if you want to play solider!

With Battlefield‘s unfortunate shift towards militarized police, and the many real-life stories of soldiers and police crossing the line in the name of peace because their “enemies” are dehumanized in every form of media possible, having fans of this problematic genre sign up for the real thing is probably the worst idea imaginable.

Whether playing soldier or cops and robbers, games that aim for a realistic immersive experience while drawing the line at encouraging even a moment’s reflection on the consequences of their actions, sells players, and developers’ own efforts, short. Contrast that with Spec Ops: The Line‘s controversial twist which dared to not only cross that line, but picked it up and tied it around players’ necks, forcing the confrontation.

Of course, that game sold a fraction of any Call of Duty or Battlefield release, and remains an exception in the genre. And therein lies the problem, no different from Hollywood—money talks and very few big publishers are in the business of making art for more discerning players, at least in the shooter genre.

Do you like email?

Sign up here to get my bi-weekly "newsletter" and/or receive every new blog post delivered right to your inbox. (Burner emails are fine. I get it!)