During the DOJ v PRH antitrust trial, one of the controversial data points that had many in the industry scratching their heads was the marketing spend of Penguin Random House. PRH US CEO Madeline McIntosh testified that it comprises 2 percent of revenues, which was widely calculated as $55 million on annual sales of about $2.7 billion.

This number quickly became fodder for those who believe traditional publishers don’t know what they’re doing and add little value to an author’s career—an unfortunate but understandable takeaway from the trial overall. It was even a point of contention during the Hot Sheet’s roundtable discussion, in which I found myself reluctantly in the position of “defending” PRH.

Math is important, even in a creative industry like publishing. What numbers are publicly available to establish a clearer picture about PRH’s marketing spend and what it means for authors?

On its face, dedicating only 2 percent of revenue to marketing seems undeniably embarrassing for the largest trade publisher in the US, which publishes about 275 imprints and 15,000 new print titles annually. In the context of a trial where you’re attempting to downplay your strengths while arguing there’s no correlation between large advances and marketing spend, under oath it might make sense to put a potentially embarrassing metric like that on the record.

PRH total annual revenue includes book sales, distribution fees, and rights and licensing fees; sales of its own products in 2021 generated 95.3 percent of overall revenue. If we apply that percentage to PRH US’s 2021 revenue ($2.51 billion at current exchange rates) that leaves $2.39 billion in actual book sales, 2 percent of which is $47.8 million.

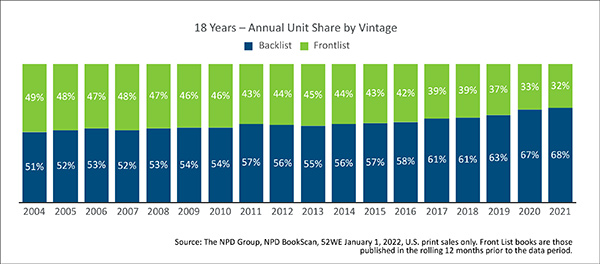

Of course, PRH didn’t make $2.39 billion solely from books published in 2021, because backlist sales across the industry have represented the majority of overall book sales since 2004. They have only increased over time, hitting a high of 68 percent last year. HarperCollins CEO Brian Murray noted during the trial that “the size of a publisher’s backlist is critical to a publisher’s stability. … It’s almost like an annuity.” While PRH has one of the strongest backlists in the industry—a position they cemented when Random House merged with Penguin in 2013 and are looking to bolster further with the acquisition of Simon & Schuster—they trailed NPD BookScan’s average, with “only” 58 percent of 2020 revenue coming from backlist sales in 2020.

The annuity analogy is an insightful one for backlist because it implies a reliable, predictable stream of annual revenue, the exact opposite of the frontlist, which is more like betting on penny stocks. Generally speaking, the backlist doesn’t get dedicated marketing spend because it doesn’t need it, so you have to subtract backlist revenue to get a clearer sense of what percentage of revenue PRH’s marketing spend actually represents.

Assuming PRH continued to trail the industry average in 2021 by the same margin, 59 percent of their book sales were backlist; $2.39 billion in actual book sales becomes $979.9 million in frontlist revenue, and $47.8 million in marketing becomes a still underwhelming but more realistic 4.9 percent of frontlist revenue.

For the 15,000 print titles PRH claims to publish annually (an unknown but not negligible percentage of which are reprints and new editions that get no marketing spend), that’s an average of $3,187 per print title in dedicated marketing spend. Average, of course, means some books get much less than $3,187 in marketing spend, and there’s plenty of evidence confirming bestselling and celebrity authors get much more than that.

This math suggests that plenty of newly published books are, in fact, getting no dedicated marketing spend at all—including the vast majority of digital exclusives—a sobering realization for anyone chasing a Big Five book deal.

Marketing tactics can look very different in different industries, but the common denominator is relatively universal: Ensure your products or services are visible, accessible, and comprehensible to your target audience(s). Comparing book marketing to consumer packaged goods, software as a service (SAAS) products and services, or even other forms of media isn’t comparing apples to apples.

Traditional corporate publishers like PRH have several marketing levers available to them, and because of their size and efficiencies of scale, they’re relatively inexpensive and are often taken for granted. The majority of these are systemic, tied to generating pre-publication buzz from key intermediaries long before the average reader ever hears about the book. Many of these expenses don’t hit an individual book’s P&L but are instead rolled into corporate overhead, and their impact can be far more effective than any paid marketing campaign.

Industry conferences and advance reader copies (ARCs)—both of which do the heavy lifting for most books’ pre-publication buzz—are relatively modest, predictable expenses for corporate publishers, and the pandemic’s impact on both are part of the reason backlist sales surged even more over the past two years. Key industry influencers rely heavily on conferences and ARCs as early indicators of which books they should pay attention to, and that attention drives interest from wholesalers, booksellers, librarians, and, eventually, readers. This process favors the largest publishers, ensuring even their least marketed titles get more pre-publication opportunities than books from smaller publishers and self-published authors who have neither the budgets nor relationships to effectively take advantage of them.

Many traditional publishers of all sizes have also invested in a variety of direct-to-consumer marketing efforts, from social media and email lists to proprietary databases of consumer information and insights that inform everything from acquisitions to marketing channels. In my experience, PRH is generally considered to have the largest, most sophisticated operation in the industry, from a pre-publication perspective. Most of this marketing is behind the scenes and invisible to the average reader. (Open Road Media’s Ignition service is arguably the most sophisticated backlist operation.) Opportunities from these owned media channels and proprietary data typically don’t hit individual P&Ls as dedicated marketing spend, but their impact can mean the difference between midlist success and obscurity.

Traditional publishers also tend to get most of the earned-media opportunities from influential external partners (e.g., New York Times, Entertainment Weekly, Publishers Weekly), in the form of featured reviews, interviews, and essays by their authors. Some of this is driven by advertising relationships in asymmetrical, not quite pay-to-play scenarios, where marketing spend for A-list authors opens the door to editorial opportunities for midlist authors from the same publisher. None of this hits the smaller author’s individual P&L as marketing spend.

When it comes to paid marketing, the titles lucky enough to receive $3,187 in dedicated marketing spend are most likely getting paid social and/or search engine marketing or a basic digital campaign with a media partner. Sometimes this is just vanity marketing, a way to show the author (and their agent) that their book is being supported and to provide something for them to boost via their own platforms. More often than not, the investment is in response to pre-publication buzz—an attempt to catch a wave—which could then lead to more marketing spend. Very few authors get in-person book tours, full-page ads in The New York Times, or posters in the subway. When they do, it’s rarely someone who doesn’t already have a built-in audience, a proven track record of backlist sales, or the attention of a major influencer.

It’s a reality McIntosh controversially alluded to during the trial when she said, “Paid marketing is the least effective way to generate sales.”

Bottom line: “Everything is random in publishing,” said Penguin Random House CEO Markus Dohle during the trial. That comment was openly mocked in some circles—rightfully so for the whole quote—but there was a kernel of truth to it. Part of the reason book publishing is legitimately considered somewhat random is that, beyond the traditional pre-publication levers, the best marketing happens organically via that elusive word of mouth that kicks in after a book finds its audience and which can be amplified via paid marketing efforts. Corporate publishers have a significant advantage in building pre-publication buzz, meaning $3,187 in marketing spend from the right PRH imprint could have more impact than $31,870 from another publisher. Conversely, being one of 15,000 PRH books competing for $3,187 means the odds are never in your favor, especially if you’re not building from a previous success, undeniable platform, or the right industry relationships.

Whether PRH’s marketing spend is 2 percent or 4.8 percent of revenue, the more important takeaway from the trial was the explicit confirmation that all books are not marketed equally, and getting a book deal from a Big Five imprint could be worse than going with a smaller publisher, regardless of the size of the advance.

[NOTE: This article was originally commissioned, edited, and published by The Hot Sheet and is republished here with permission. If you’re an author looking for intelligent insights on the important issues affecting the publishing industry, you should definitely subscribe.]

[NOTE: This article was originally commissioned, edited, and published by The Hot Sheet and is republished here with permission. If you’re an author looking for intelligent insights on the important issues affecting the publishing industry, you should definitely subscribe.]

Do you like email?

Sign up here to get my bi-weekly "newsletter" and/or receive every new blog post delivered right to your inbox. (Burner emails are fine. I get it!)