Back in 2009, I was in the interesting position of launching a conference intended to help book publishers navigate the digital transition allegedly being driven by the rise of ebooks, which pundits, technologists, and credulous journalists were gleefully declaring signaled the death of print and traditional publishing models. For 18 months, from its announcement in late summer of 2009 through its second edition in January 2011, I was Digital Book World’s Chief Executive Optimist, a journey I’ve written about before and won’t rehash here.

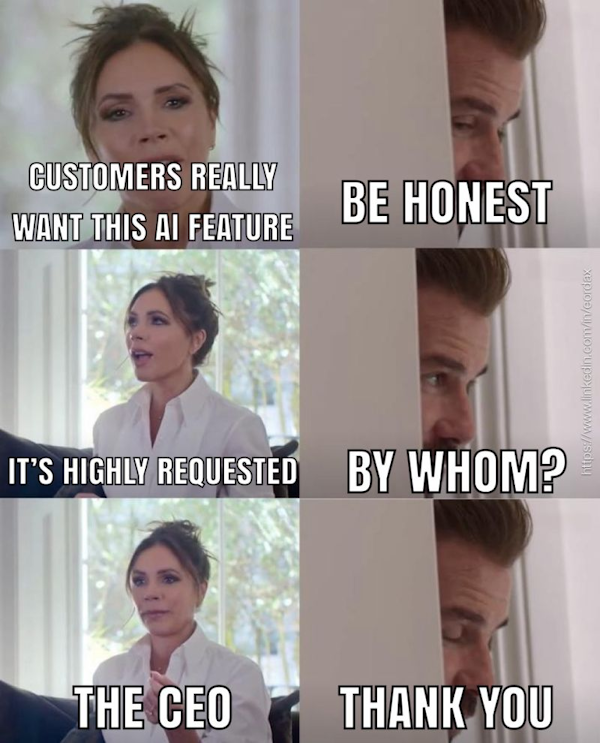

What’s relevant about my experience with DBW when looking at what’s happening with AI in publishing is the fact that we’ve seen this movie before — from enhanced ebooks to pivot to video to NFTs — and it always ends the same way: bad business decisions influenced by serial grifters negatively impacting everyone except the craven, short-sighted executives making them.

Unsurprisingly, few ever suffer any tangible consequences for those bad decisions, often being rewarded with the chance to make another one.

The AI hype train is reaching predictably ridiculous extremes in a desperate attempt to force acceptance of its “inevitable” narrative, and it’s partly because credulous journalists who should absolutely know better by now happily platform the worst of this nonsense.

The first camp, which I associate with the external critics, holds that AI is fake and sucks. The second camp, which I associate more with the internal critics, believes that AI is real and dangerous. Today I want to lay out why I believe AI is real and dangerous.

“The phony comforts of AI skepticism,” Casey Newton

Every time I consider paying for a subscription to Newton’s sporadically insightful newsletter, he reminds me of his Achilles heel: he’s either a trusted mark, a sucker for access, and/or a true believer who’s convinced himself that he’s an objective observer. Last year, while covering Substack’s Nazi Bar problem, he dithered over abandoning the platform himself, partly in the naive belief that he could pressure them to not be who they’d proudly explained they really were multiple times — but mostly because moving might be a financial hardship for his “independent” journalism. Ironically, when he finally made the move, he subtitled the announcement and explanation with, “We’ve seen this movie before — and we won’t stick around to watch it play out.”

And yet, his recent coverage of AI not only suggests he hasn’t seen this movie before, but maybe he’s never even heard of movies to begin with?

At first glance, I appreciated Newton’s attempt to analyze the raging AI debate, but starting with the false dilemma that there are only two POVs undercut what he says he was trying to accomplish with the rest of this article. Plenty of people think AI is real AND sucks AND its potential needs to be taken seriously (including some of my favorites: Baldur Bjarnason, Timnit Gebru, and Vivienne Ming), primarily because most of the people making key decisions related to it have unscrupulous motives and/or incentives — as has been true with every new technology.

Newton does some good reporting at times, but his credulity shines through whenever he shifts to analysis, always willing to give the people behind questionable technologies the benefit of the doubt despite that doubt proving correct more often than not. (In his own words, again: “We’ve seen this movie before…“) Ironically, his original post was free, while his follow-up addressing the critical response was a paid post, so at least he’s a good marketer, I guess.

AI in Publishing

I’ve spent the vast majority of my career in publishing (magazines and books), and every step forward I took was paved by my comfort with technology because, despite misleading generational narratives, it was us Gen X kids who grew up during the digital transition. From the earliest days of personal computing and video games to the evolution from Web 1.0 to 2.0 to mobile phones that ensure we’re never truly disconnected from work — we rode the wave from analog to digital, and our experience with the former often provides more nuanced insights into the latter.

My first full-time job in publishing was thanks to my willingness to teach myself QuickFill, a subscription database that powered a single publication that was left adrift when the only person on staff who knew how to use it unexpectedly quit. I was two days into a temp role when that happened (October 1993), and I seized the opportunity. Nine months later I was hired and my career in publishing began.

Over the years, I’ve watched new technologies, products, and services for publishers and marketers (and consumers) come and go, and I’ve gotten pretty good at smelling vaporware and grifters from a mile away. I’ve also learned publishing executives are generally the easiest marks in any industry, willing to blindly entertain every new shiny that claims it will democratize or disrupt their business.

The fast-evolving AI sector could deliver new types of formats for books, [HarperCollins CEO Brian] Murray said, adding that HC is experimenting with a number of potential products. One idea is a “talking book,” where a book sits atop a large language model, allowing readers to converse with an AI facsimile of its author. Speculating on other possible offerings, Murray said that it is now possible for AI to help HC build an entire cooking-focused website using only content from its backlist, but the question of how to monetize such a site remains.

All the various AI products are “kind of interesting, but I don’t know how you market, price, or sell them,” he said, adding that he can’t predict when these products “may move the needle on our overall economics.” Instead, HC’s immediate focus is on using AI to help its teams work more efficiently in such departments as sales, marketing, and editorial, Murray said: “We have dozens of initiatives to empower efficiency.”

“HarperCollins CEO Brian Murray Talks Hot Print Book Sales and AI,” Jim Milliot

Back in the DBW era, I was often in the awkward position of being a contrarian voice — either in my own writing, or op-eds I sourced from others in the industry — particularly on the actual impact of Apple’s entry into the ebook market. One notable example was a relatively innocuous look at ebook sales trends in late-2010, where I asked the question, “Does Ebook Growth Mask Market Share Declines?” That article almost got me fired when our primary programming partner objected to my contradicting the narrative he was heavily invested in pushing, culminating in one of the most awkward dick-measuring contests I’ve ever witnessed between him and my boss’ boss, the latter of whom ultimately defended me. (IYKYK)

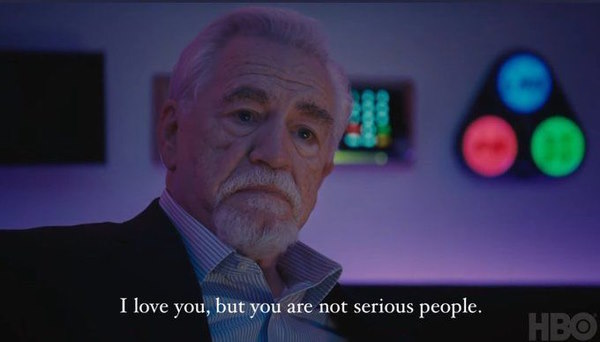

Whenever I see executives like Murray vaguely mention the opportunities for AI in their own houses, I feel as bad for their staff as I did during the DOJ v PRH trial where several executives went on record basically saying they had no idea how to run their businesses. There’s a growing body of research that shows AI’s alleged productivity benefits are generally limited to less-skilled workers, creating a scenario where you limit their potential to actually gain experience and improve their skills, with rapidly diminishing returns on the productivity you think you’re increasing.

As Vivienne Ming put it last year, “The person you got on Day 1 is the person you have on Day 1,000.”

It’s also always important to follow the money, connecting the dots between pundits/consultants, industry executives, and who’s investing in AI initiatives. From former PRH CEO Markus Dohle raving about AI’s potential without disclosing his financial relationship with Shimmr, to Simon & Schuster owner KKR’s “$50 Billion Strategic Partnership to Support AI Growth Through Investments in Data Centers and Power Generation,” the only thing that’s inevitable about AI in publishing is that a lot more bad decisions will be made that have a negative impact on individual authors, editors, marketers, designers, and other people doing the actual work, while investors massage spreadsheets to maximize value for their shareholders.

FOH.

Do you like email?

Sign up here to get my bi-weekly "newsletter" and/or receive every new blog post delivered right to your inbox. (Burner emails are fine. I get it!)

FOH indeed. (Thank you)

It does seem that Gen X is the last group of folks with any real anti-bodies to fight all the digital crud. The siren song of AI tools is too simply (and falsely so) tied to cost cutting and “simply doing more with less”. There needs to be a real-world alternative for C-Suite to consider, but what it is… I have no idea… I mean what is the counter argument to all of the ads, conferences, webinars, etc. touting how easy and cheap AI tools are? Maybe if publishers include enough of the team in decision making and let adoption be from the bottom up publishers will fair better. I’m also proud to say that I now know what FOH means. So thanks for that!

I like how McAveney framed it at PIF, as a bottom-up approach rather than top down. If the use cases are clear, people will find ways to leverage new tools because the advantages (and disadvantages) will be clear. I haven’t seen something pushed as aggressively as AI since the pivot to video nonsense a decade ago, which was primarily driven by Facebook outright lying about metrics and media executives never questioning them, not unlike the vanity social metrics it was all built upon.