The Problem With Self-Publishing

HarperStudio — one of a handful of publishers who really seems to understand how to use the internet and social media — is running a web poll on their home page right now that asks: “Are you less likely to read a book if it is self published?”

As I write this, there have been 15 votes and “YES” is winning with 60% of them. Of course, it’s not the least bit scientific (and doesn’t claim to be), but I wouldn’t be going too far out on a limb to predict that, barring some targeted effort by Author Solutions, no matter how many responses they end up getting, “YES” will win, because the phrasing and context of the question favor that response.

I voted “NO” because I know better.

Unless you’re a traditional publisher with a vested interest in the status quo, or an insecure writer who puts a lot of stock in the name of one’s publisher, there’s really nothing wrong with self-publishing that’s not a problem for the publishing industry in general:

Too many mediocre books being published? Check!

Minimal marketing support for the vast majority of books being published? Check!

Too much up-front money being put towards vanity projects? Check!

Lackluster editing and/or pedestrian design? Check!

Huge, out-of-control egos in need of a reality check? Check!

Except for comic books, very few publishers have the kind of brand recognition that can influence sales at the retail level. Their strength is primarily on the backend, their ability to get books onto bookstore shelves and into influential critics’ hands. Ask 100 people in a bookstore who publishes Stephen King, or Stephenie Meyer, or the “For Dummies” series, though, and you’ll likely get a blank stare and a shrug from 75% of them.

My decision to read a book comes from a combination of three things: personal interest in topic/genre, recommendations, and sampling — and I don’t think I’m highly unusual in that regard.

Only the latter point is really influenced by a traditional publisher, as those are the books most likely to be on a bookshelf available to browse and sample, but between Amazon’s “Look Inside”, free Kindle samples, and smartly designed author (or publisher) websites, even that isn’t an obstacle for any book, self-published or not, that hits my radar via the other two criteria. In fact, the ability to sample a book digitally and online opens it up to a much wider audience than having 1-2 copies in a bookstore, buried in alphabetical order between a bunch of similarly unknown authors’ names and unimaginative titles.

Distribution and visibility aside, the most commonly noted “problem” with self-publishing, of course, is that self-published books mostly suck and there’s so many of them being cranked out every year that finding a good one is a near impossible and not terribly worthwhile task. While mostly true, it ignores the larger reality that taking a stroll through Barnes & Noble or Borders in search of a good book can be a similarly frustrating and unfruitful task.

The fact of the matter is that writing a book is hard; writing an objectively good book is even harder; and writing one that can survive the subjective tastes of influential critics, well, that’s practically impossible.

Just ask Stephenie Meyer, best-selling author of the Twilight series, who got ripped by Stephen King earlier this week in USA Today: “The real difference is that Jo Rowling is a terrific writer and Stephenie Meyer can’t write worth a darn. She’s not very good.”

(Side note: In college, the first time around, before I ended up in the Army, I was writing a paper defending the work of Stephen King against criticisms that he was a popular hack and his work had no literary merit. This was back in 1990, and most people, including my English professor, agreed and thought I was crazy. I’ve never read any Potter or Twilight novels, but King’s criticism of Meyer’s writing is one I’ve seen made many times, in a variety of places, of both of them.)

The vast majority of self-published books are vanity projects, most by authors who never bothered to attempt to go the traditional route because their primary goal was getting the finished product in their hands, not the “validation” and “legitimization” so many tend to associate with a traditional publisher. As a result, the closest they’ve come to being edited is a cursory reading by a couple of friends or family members followed by compliments and encouragement to pursue their dreams. It’s like poetry slams where 10s are mandatory; most of it is self-indulgent dreck with a narrowly defined audience of one.

Less-typical, but often lumped in the same category, is the wannabe author whose work simply wouldn’t get past the critical eye of an editor or agent, and goes the self-publishing route of out of frustration, usually in hopes of landing a copy on an influential someone’s desk to become the next one-in-a-million success story who nails a lucrative publishing deal after proving their worth. While this certainly does happen, it’s rare because of the stereotypical stigma that still defines self-publishing for those on the inside of the industry.

Finally, and for whom self-publishing tends to work the best, is the ambitious author who understands that, no matter who their publisher is, they’re going to have to bust their ass to market their book and hand-sell it to as many people as possible, in-person and online. These are most often non-fiction writers with a niche expertise and poets — and to a lesser degree, comic book creators — who have the ability, innate or developed, to perform in front of a crowd of tens or hundreds (or thousands) and schmooze just as comfortably on a one-on-one level.

These authors tend to have built a platform for themselves over time — something almost every traditional publisher pretty much requires these days — and know how to use it and continually nurture it.

For them, there aren’t any problems with self-publishing at all, as they stand to reap significantly greater rewards for their efforts. It’s traditional publishing that’s problematic, where expectations for the same level of author effort come with minimal support in return, and a much smaller cut of the sales of each book.

Related

Discover more from As in guillotine...

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

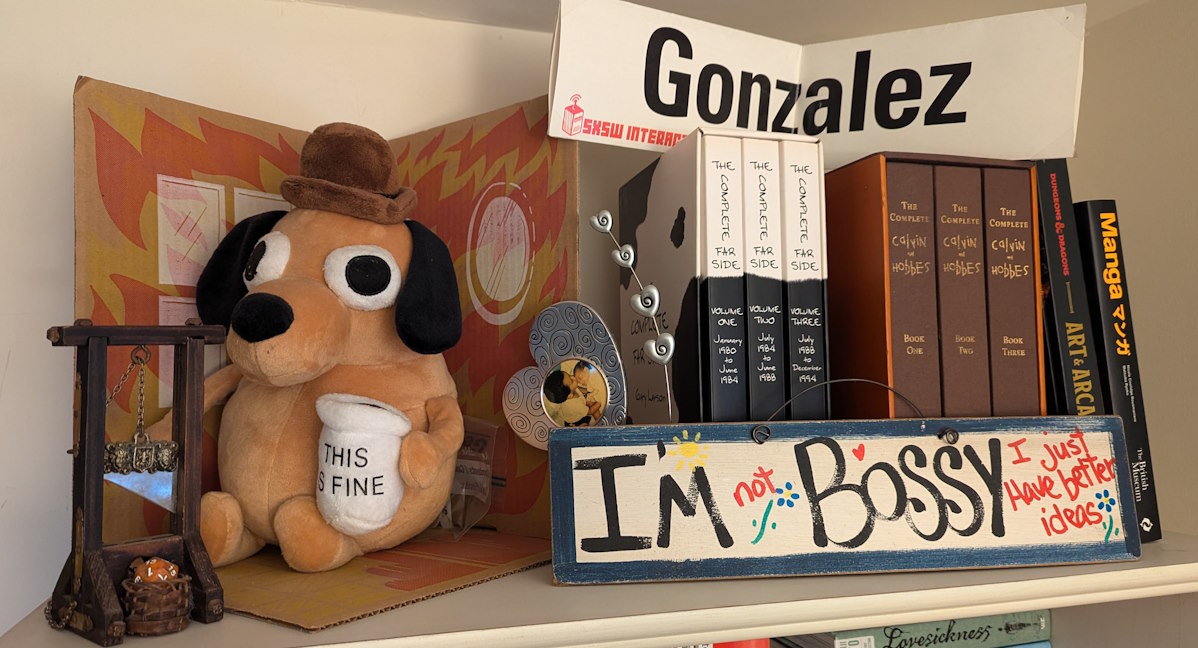

Written by Guy LeCharles Gonzalez

Guy LeCharles Gonzalez is the Chief Content Officer for LibraryPass, and former publisher & marketing director for Writer’s Digest. Previously, he was also project lead for the Panorama Project; director, content strategy & audience development for Library Journal & School Library Journal; and founding director of programming & business development for the original Digital Book World.

5 comments

Keep blogs alive! Share your thoughts here.Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Interesting post, Guy. And thanks for your kind words about HS.

If a self published book was beside a book from a big house — how could a potential reader tell the difference?

Wicked post.

Bookstore managers tell me the first clue to self published vs. 'big house' publisher is cover design and the second is errors in copy. They say they can't tell my book is self published because I spent the money on a quality cover design and copy editing.

While you can't always judge a book by its cover, first impressions are critical and amateurish cover design and sloppy editing limit a lot of self-published books from reaching a wider audience, especially via traditional distribution channels. It's worth noting that major bookstore buyers have a lot of influence over traditional publishers' cover design and format choices, too.

Agreed, first impressions are critical. It's really not that hard to be a successful self publisher, speaking as one who has moved from 'self' to 'independent' with an actual roster of writers now. You need a good website (simple and easy to navigate), an outside eye to catch editing mistakes (it's amazing how they get missed) and a simple, simple design.

Further, a defined target market is essential. I think niche markets are where the self publisher thrives. A well defined narrow market is always going to be easier to hit and maintain contact with than to try to compete with mass distribution….