In the comics world, there are many sacred cows, and Alan Moore and his impressive body of work is perhaps one of the biggest in the herd

In the comics world, there are many sacred cows, and Alan Moore and his impressive body of work is perhaps one of the biggest in the herd

While I’m not a fan of sacred cows—the very suggestion often taints my first impression the same way my High School required reading lists did—I do have fond memories of Moore’s ground-breaking Watchmen maxi-series, serialized back in 1986 during the peak of my first go-round as a comics fan, before a looming adulthood started offering new and more varied distractions. As a result, V for Vendetta, which began serialization a year later, never hit my radar, and I picked it up for the first time last summer in anticipation of the movie.

I’d reread Watchmen a year or so earlier and, while able to appreciate its much-deserved place in comics history for Moore’s real-world spin on superheroes, felt it hadn’t aged well at all. Despite Time magazine honoring it as one of their Top 100 Novels last year—the only graphic novel on the list, BTW—I would never suggest it to someone who’s new to comics and looking for something to read. Considering I’m pretty sure that I didn’t actually finish rereading it, and as I type this, can’t remember any of the specifics of the story, I don’t think I could wholeheartedly suggest it to modern superhero fans, either.

[Mild spoilers ahead.]

V for Vendetta, on the other hand—while similarly dated and liberally incorporating elements familiar to any fan of the vengeance seeking, flush with resources anti-hero—holds up remarkably well all these years later. It’s a flawed story, mind you, as Moore slips back and forth between compelling melodramatic fiction and hamfisted polemic (similar in some ways to Fahrenheit 911), but the overall result is that of an incredibly engaging tale—part revenge thriller, part political potboiler, part police procedural—that takes the reader on an emotional roller coaster ride before ending on a somber, if obliquely hopeful, note. Moore ably juggles a large cast of reasonably fleshed-out characters, some moreso than others, and multiple intertwining subplots, and the sum is, without question, greater than its individual parts.

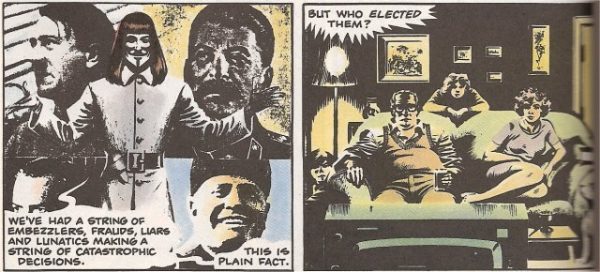

The underlying theme throughout is that of individual choice, and how the choices we make, or don’t make, affect the world around us. Set in 1997, in a post-apocalypse, fascist England that would make George Orwell smirk, V explains, during a take-over of the state-run television network:

“We’ve had a string of embezzlers, frauds, liars and lunatics making a string of catastrophic decisions. This is plain fact. But who elected them? … You have encouraged these malicious incompetents, who have made your working life a shambles. You have accepted without question their senseless orders.”

Reading that particular passage, I pictured the Wachowskis’ eyes lighting up, recalling the red pill/blue pill scene in The Matrix, and the tickle in the back of my own head the first time I saw it, wistfully contemplating the philosophy behind the idea. At that point, I was pretty sure they’d do a good job with the movie, and, for the most part, they did, despite Moore’s furious objections that ultimately led to his removing his name from the credits (both of the movie and future printings of the book, I believe) and signing over all royalties to his collaborator, the artist David Lloyd, who did a stellar job bringing his story to life the first time around.

The movie is an adaptation in the most literal definition, “a composition rewritten into a new form,” and anyone looking for a panel-by-panel, Sin City-style production is going to be sorely disappointed with it. If anything, whereas the book fits the proverbial “whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” the movie is the opposite, featuring several great parts that come together in a satisfying, if not stellar, whole.

The Wachowskis, necessarily so, have flattened Moore’s story, jettisoning many of the subplots and streamlining the story’s two primary threads—V’s vengeance and Evey Hammond’s enlightenment. They’ve also revamped most of the characters; updated the setting into the 21st century and incorporated several overt (and, at times, hamfisted) references to a world led into ruin by the United States of America and its War on Terror™; and completely rewritten the final act. The latter point is, perhaps, the most contentious, as it strays from Moore’s embracing of anarchy as a solution and posits a vague democracy via agitprop scenario that a more cynical person might point out is simply an ill-fated frying pan to the fryer choice. Of course, some might say the same about choosing anarchy, so in my mind, it’s a minor quibble.

The larger flaw, however, lies in their unnecessary addition of an overt romantic link between V and Evey, and the shift to making V’s beef with the government a much more personal one than it is the book. Both additions serve to weaken the ending somewhat, with Moore’s being stronger despite the road to getting there being infinitely more implausible. (Brother Eye, anyone?) Overall, though, most of their tweaks actually improve upon the story, not the least of which is adding a much-needed bit of a sense of humor to the proceedings, as with an early scene featuring V cooking breakfast in a floral print apron.

Natalie Portman pretty much carries the movie on her slim shoulders, though she is assisted by several spot-on supporting performances, especially Hugo Weaving’s, who deserves some recognition for pulling off what must be one of the most difficult challenges for an actor, completely hidden beneath a mask that gives no hint of the man underneath. It’s all body language (and camera angles), and though at times I kept hearing Agent Smith in the back of my head, I think he did a great job. Stephen Rea, as Chief Inspector Finch, does a wonderful job, too, as the detective who keeps on digging despite knowing he might not like what he turns up: “If our own government was responsible for the deaths of a hundred thousand people… would you really want to know?”

Portman, though, was a revelation, shaking off the horrid Star Wars trilogy in a way Hayden Christensen can only dream of. Of particular note is the scene where she is being tortured for information about V and does most of her acting with her eyes. It’s a powerful scene in the book, perhaps the most powerful, and the Wachowskis transfer it to the screen pretty much intact. If I were her agent, I’d be cutting that scene onto a DVD and sending it out to every voting member of the Academy next Winter.

V for Vendetta is, at its heart, a solidly constructed popcorn thriller, nothing more, nothing less. While it uses political themes primarily as window dressing for telling a good yarn—the movie moreso than the book, though Moore’s take on it wasn’t really that much deeper, simply more focused—it is definitely more agit-prop than legitimate political statement, akin to my getting on stage and reading an angry poem about life under Bush, or Howard Dean’s opportunistic anti-war stance during the Democratic primaries back in 2004. It may be preaching to the choir at some level, but as has been pointed out many times over the past six years, “The choir ain’t singing!”

V for Vendetta is about ideas more than solutions, and V himself is an idea, a symbol, a metaphor writ large. “Ideas are bulletproof,” explains V in the book.

His identity remains a mystery, in both the book and the movie, and that is purposeful (though in the book, it’s made clear in Dr. Delia Surridge’s journal that V is a man, and not Evey’s father, and IIRC that’s carried over to the movie, too). There’s a sequence at the end of the book that’s not used in the movie, where Evey debates removing V’s mask, and it repeats four times with four different results, the final scenario revealing her own face. The movie does something similar with Inspector Finch’s character, whose transformation is the most relatable to the general audience, as he goes from loyal party man to skeptic to, in the end, siding with V (in spirit, at least).

That is ultimately the message I took from the story, that each of us has a choice — the blue pill or the red pill, if you will—that any one of us, no matter where we start, can become V (or Guy Fawkes, or Nat Turner, or José Marti) if we make the choice to do so. It’s agit-prop for the summer blockbuster crowd; too simplistic, perhaps, for the more politically savvy, but at just the right level for the average audience member more focused on making ends meet and putting food on the table than dissecting the nuances of political ideologies. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Considering the timelessness of Moore’s original story, despite being written in the same era as Watchmen, if I had a vote, I’d substitute V for Vendetta on Time‘s Best 100 Novels list. It’s more intricate, more engaging, and, in many ways, more accessible, and I highly recommend it to anyone who’s not turned off by sequential art as a form. (ie: My wife won’t be reading it.)

As for the movie, recognizing it for the densely layered popcorn action thriller it is, it gets two thumbs up from me, as well as a suggestion to not read the book first if you haven’t already. Judging from my wife’s confused reaction to it, I feel like there might have been some information that I caught because I’d read the book the day before. Nevertheless, it’s as entertaining a 2+ hour movie experience as I’ve had recently, and I’ll definitely be buying the inevitable special edition DVD whenever it comes out.

NOTE: This review was edited from my comments in an email roundtable on V for Vendetta, put together by the November 3rd Club, and may seem slightly disjointed as a result. The full discussion should be posted sometime later this week, and I’ll add the link to it when I get it.

Do you like email?

Sign up here to get my bi-weekly "newsletter" and/or receive every new blog post delivered right to your inbox. (Burner emails are fine. I get it!)

guy. alex cahill from the new radio here. i have precisely the same verdict on the movie as you! seriously, i think ‘densely layered popcorn action thriller’ pretty much covers it. kudos.

by the way, i’ve been trying to get a hold of you via email and to no avail. did you get the book i sent you, *the last island*? i’m dying to hear what you thought if you did, and i can send another along if you didn’t. lemme know!

alex cahill

a_rowdy_c@newradiocomics.com